Frequency Modulation with Synthesizers

- Sean Graves

- Jan 30

- 4 min read

In the vast and ever evolving world of sound synthesis, Frequency Modulation (FM) stands out as a powerful and distinct technique. It's responsible for some of the most iconic and unique sounds in music history, from the piercing bells of the Yamaha DX7 to the rich, complex textures found in modern electronic music. But what exactly is FM synthesis, how does it work, and why does it create such characteristic tones? This deep dive will unravel the mysteries of FM synthesis, making it accessible to anyone with an interest in sound.

What is Frequency Modulation?

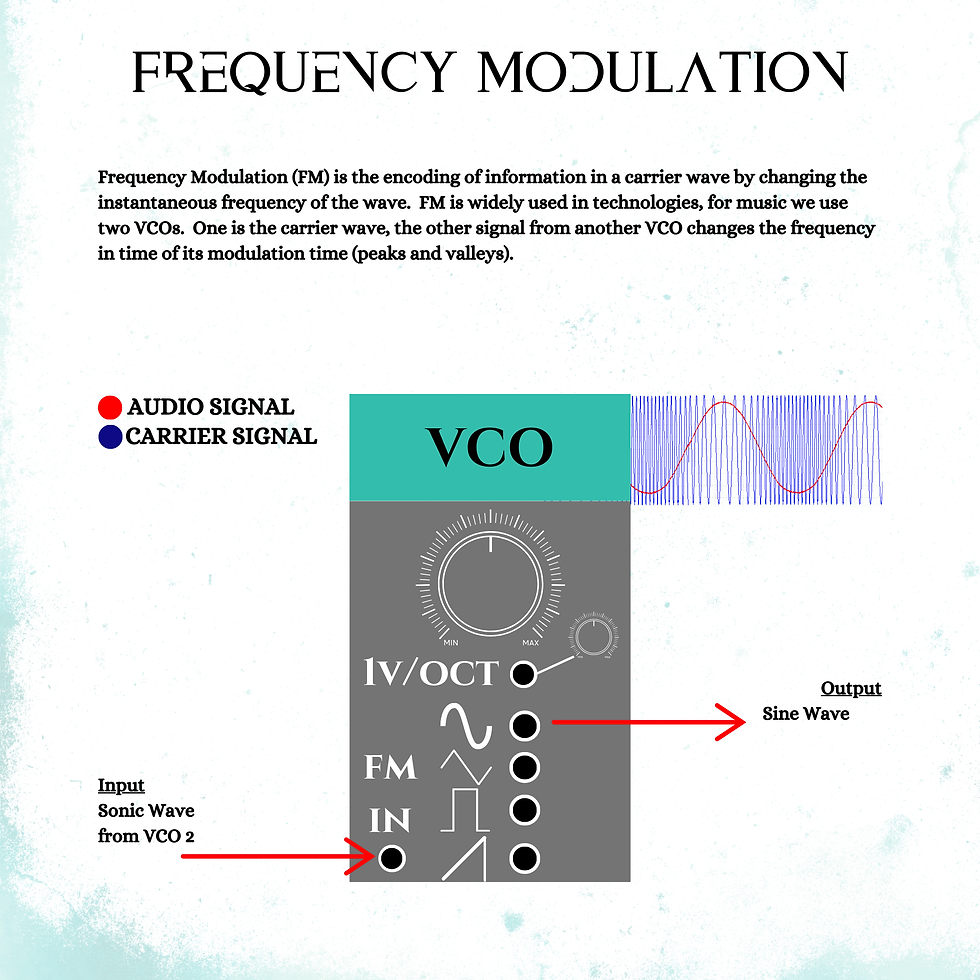

At its core, FM is the process of varying the frequency of one waveform (the carrier) with the amplitude of another waveform (the modulator). Think of it like this: if you have a steady tone, and then another fluctuating tone starts to push and pull on the first tone's pitch, causing it to rapidly go up and down. That rapid change in pitch is what we perceive as new, complex timbres, rather than just a simple vibrato.

In the context of synthesizers, these waveforms are typically generated by oscillators. An oscillator is an electronic circuit that produces a repetitive alternating current, which, when converted to sound, becomes a continuous tone.

How Does FM Synthesis Work?

Let's break down the mechanics of FM synthesis with a bit more detail:

The Carrier and Modulator Oscillators

Carrier Oscillator (C): This is the oscillator whose frequency is being modulated. Its fundamental frequency will determine the perceived pitch of the sound.

Modulator Oscillator (M): This oscillator's output amplitude is used to control the frequency of the carrier. The frequency of the modulator determines how fast the carrier's pitch is wiggling, and the amplitude of the modulator determines how much the carrier's pitch is wiggling.

The Modulation Process

When the modulator oscillator is introduced to the carrier oscillator, the amplitude crreates a continuous shift in the carrier's frequency.

Modulator's Amplitude: As the modulator's waveform goes through its cycle (from its peak, down through zero, to its trough, and back to zero), its amplitude changes.

Carrier's Frequency: This changing amplitude is then applied to the carrier. When the modulator's amplitude is positive, it pushes the carrier's frequency up. When the modulator's amplitude is negative, it pulls the carrier's frequency down. The greater the modulator's amplitude, the greater the deviation in the carrier's frequency.

The Key Parameters

Several key parameters influence the sound production by FM synthesis:

Carrier Frequency: Sets the basic pitch of the sound.

Modulator Frequency: Determines the rate at which the carrier's frequency is modulated. This is often set in a ratio to the carrier frequency (1:1, 1:2, 2:3). These ratios are crucial for creating harmonic or inharmonic sounds.

Modulation Index (or depth): This is perhaps the most critical parameter. It represents the amplitude of the modulator and thus controls how much the carrier's frequency is deviated.

Low Modulation Index: Produces sounds with fewer overtones, often resembling simple waveforms or adding a subtle richness.

High Modulation Index: Generates a vast number of sidebands, leading to complex, often metalic, bell-like, or noisy timbres.

Algorithms

In more advanced FM synthesizers, especially digital ones like the Yamaha DX7, multiple carrier and modulator oscillators (often called operators) can be arranged in various algorithms. An algorithm defines how these operators are connected, determining which operators act as carriers and which cat as modulators, and how they interact with each other. This allows for incredibly intricate sound design possibilities, as one modulator can modulate another, or multiple modulators can affect a single carrier.

Why Does FM Synthesis Create Its Unique Tones?

The distinctive character of FM sounds arises from the creation of sidebands.

Sidebands and Harmonics

When the frequency of a carrier wave is modulated, new frequencies are generated that are not present in either the original carrier or modulator. These new frequencies are called sidebands, and they appear as pairs above and below the carrier frequency, spaced apart by the modulator's frequency.

The crucial aspect of FM synthesis is that the amplitude of these sidebands is directly affected by the modulation index.

Simple Waveform: With a very low modulation index, you might only hear the carrier frequency, possibly with a few subtle sidebands.

Complex Timbres: As the modulation index increases, more and more sidebands are generated, and their amplitudes change dramatically. These sidebands can become very prominent, even exceeding the amplitude of the original carrier frequency.

Inharmonicity: If the carrier and modulator frequencies are not in simple whole number ratios, the sidebands generated will not be harmonically related to the carrier. This leads to inharmonic or dissonant sounds, which are often described as metallic, bell like, or clangorous. This is a key reason why FM synthesis excels at creating percussive and bell like sounds.

Dynamic Timbres: Because the sideband amplitudes change with the modulation index, varying the modulation index over time (with an envelope generator) can create incredibly dynamic and evolving timbres. This is how FM synthesizers can produce sounds that shimmer, decay or morph in complex ways.

Compared to Other Synthesis Methods

Subtractive Synthesis: Starts with a harmonically rich waveform (like a saw or square wave) and then removes frequencies with filters. FM synthesis adds new frequencies (sidebands) to create its timbre.

Additive Synthesis: Attempts to create sounds by layering many sine waves at different frequencies and amplitudes. While FM synthesis also creates new frequencies, it does so through a dynamic interaction rather than simply stacking static sine waves.

The non-linear nature of FM (a small change in the modulation index can lead to a large and complex change in the sound) is what gives it its unique sonic fingerprint and makes it both challenging and rewarding to program.

Comments